Environmental activism and Indigenous issues in Cambodia: The role of film-based advocacy with and for young people

By Dr Pete Manning, University of Bath and Dr Rachel Killean, Queens University Belfast

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all staff at the Bophana Center and Elephant Livelihood Initiative Environment. Particular thanks go to Sopheap Chea, Rathany Koh, Jemma Bullock, and Chris Iverson. Thanks also to Paul Cooke for his ongoing support around this work. Finally, we would like to thank the Bunong community of Putrom for sharing their time and experiences with us.

Funding for this project was provided by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council and Global Challenges Research Fund (AH/T007923/1) under the “Follow on funding for impact” scheme. The parent project was Changing the Story (AH/R005354/1).

To cite this report, please use: Manning, P. and R. Killean (2021) “Environmental activism and Indigenous issues in Cambodia – film-based advocacy with and for young people”, Bophana Center, Phnom Penh.

Summary

Over the course of 2020 a group of twelve young Cambodians were provided with a bespoke filmmaking training programme and educational support about environmental and Indigenous issues in Cambodia. The project employed an iterative participatory methodology throughout. This involved giving ownership of the creative process to the young people, while encouraging them to develop their films through dialogue with the Indigenous communities that they worked with. The central aim of the project was to produce a set of films that could be used as advocacy tools to amplify awareness of the urgent, intersecting environmental harms and issues facing Indigenous Bunong communities in Cambodia. Three films were produced that explore and document these issues, including deforestation, animal welfare, and Indigenous Bunong heritage and culture.

The project, led by the University of Bath, was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Global Challenges Research Fund. It was designed in partnership with the Bophana Center, Cambodia’s leading arts-led civil society organisation, and the Elephant Livelihood Initiative Environment, an organisation devoted to supporting Indigenous communities and elephant custodianship in Modulkiri, Cambodia. Further support was provided by UK investigators at the University of Leeds and Queens University Belfast.

This report reflects on and distils key lessons from the project. These can be summarised as follows:

– Participatory filmmaking is a method that lends itself to advocacy around environmental and social justice campaigns. By centring young people as authors of stories about environmental harms and Indigenous issues, young people were encouraged to take ownership of these challenges and to engage in further advocacy around them. There is potential for the messages contained within the films to therefore ‘multiply’ within and across communities.

– The films produced on the project demonstrate the affective role of wildlife on screen as a means of generating concern for environmental challenges. By centring the relationships between wildlife and communities, the films further demonstrate the inseparability of environmental harms from challenges facing Indigenous communities.

– The films can help to promote awareness of and validate Indigenous heritage and traditions in Cambodia, where Indigenous communities are often stigmatised and misunderstood. Moreover, it is hoped that the films’ production in Khmer and Bunong can contribute to the preservation of the Indigenous Bunong language.

– Participatory methods can help to build empathy and stronger relationships within and across communities. The process and practice of filmmaking with and within indigenous communities helped to destigmatise Bunong people among the trainees.

– A key challenge is to connect local issues to wider regional and global challenges. The environmental harms and challenges for Indigenous groups that are identified in the films have strong resonances across contexts. However, young people – and others engaged in environmental advocacy – must be supported in making these links.

Introduction

Film and filmmaking have proved to be critical avenues for raising awareness about environmental challenges. High profile screen releases have helped to set and steer agendas around, for example, global heating (An Inconvenient Truth), plastic usage (Blue Planet) and marine conservation (Seaspiracy). These examples represent a particular genre of “environmental documentary” that call attention to environmental challenges, often sparking campaigns for change and action (Duvall 2017). The proliferation of environmental documentaries in recent decades has coincided with greater recognition of the intergenerational politics at play around environmental harm. Young people today will inherit the worsening impacts of multiple environmental crises and have increasing taken the lead on campaigns for climate awareness and justice at key institutional sites such as the United Nations.

In this wider landscape, our work with young filmmakers in Cambodia has sought to explore and highlight what these global challenges mean for communities at a local level. Over forty years of conflict scarred the Cambodian landscape, leading to widespread loss of forest and wildlife habitat, as well as the misuse of the country’s captive elephant population. In this period, a “war economy” included damaging extractive practices, including the sale of rainforest timber. This in turn led to the decline in the number of wild elephants and other animals in Cambodia. Since the advent of peace in 1999, development pressures and deforestation have led to the loss of 2.2 million hectares of tree cover, with serious knock-on effects for the loss of wildlife. Endangered species have suffered significant population decline, even within designated sanctuaries. Cambodia’s elephant population in particular has suffered further habitat loss. Fauna and Flora International estimate that just 400-600 wild elephants remain (Maltby and Bourchier 2011).

The challenges facing Cambodia further illustrate the inseparability of the environment from issues of social justice. Environmental activists in Cambodia have faced harassment and physical violence. Indigenous Bunong communities suffer widespread discrimination, lack access to amenities, and experience elevated levels of deprivation and illiteracy. As a forest dependent community with close historical and cultural relationships to elephants, Bunong people are particularly exposed to pressures on land titles, deforestation, and the loss of wildlife habitats. As our films show, environmental harms will always intersect with other forms of human inequality.

“…the forest is under huge pressure in Cambodia. The government has designated a protected area… but the problem is that people are cutting into these protected areas. And this is having a huge impact on the forest and wildlife that lives there” (Jemma Bullock, EVP)

Documenting environmental harms and indigenous experiences

Over the course of 2020, the Bophana Center provided training in film production and editing to a group of twelve urban, rural, and Indigenous young Cambodian students. UK Investigators, Manning, Cooke and Killean provided educational seminars on the broader social, political and ethical challenges and questions that arise around environmental harms. Staff at ELIE provided the students with training and information about working with communities in Modulkiri to sensitise the students to the challenges facing Bunong people, as well as guidance on field conduct around elephants. Over the course of multiple field visits to the Elephant Valley Project sanctuary in Modulkiri, the students planned and shot three short documentary films. An iterative methodology was adopted, in which, over multiple visits, the students could reflect on and develop their films in dialogue with local Bunong community members, participants and ELIE staff.

“What makes me interested the most is related to an old elephant, which is 70 years old. The elephant has seen so many decades. That elephant is blind and has been through the war, she is traumatized and scared. This is what I’ve learnt. Not only humans can be traumatized by the war but also animals…” (Secretary of State for the Ministry of Environment, His Excellency Neth Pheaktra)

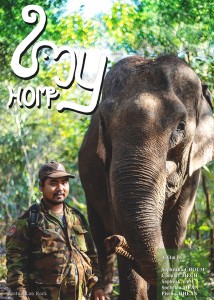

The films reflect the worldviews of the young people leading and shaping them, and their engagements with Indigenous communities and Cambodia’s remaining forest habitats. In My Home (produced by Sopheana CHOUN, Choulay MECH, Sopheak YAM, Sochetra MEAN, Pisen CHHEAN) the story of a mahout, Chheol Thouk, is used to highlight the impact of deforestation on Bunong communities and elephants. The shrinking natural habitat of elephants is explored alongside challenges to Bunong culture and cultural life, demonstrating the co-dependency of the human and other-than-human world. The film works to disrupt prevailing binaries in our ways of understanding the “human” and “nature”, as each is shown to constitute the other.

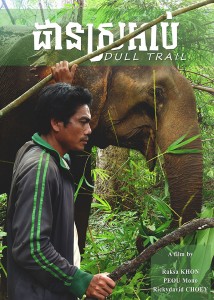

In Dull Trail (produced by Ricky David CHOEY, Mono PEOU, Raksa KHON), the story of Mae Nang the elephant is documented. Blind in one eye and traumatized from years of war and American bombs, Mae Nang learns to accept the love of her mahout, Da Chroed. The film draws attention to Mae Nang’s trauma, and the effects of Cambodia’s experiences of conflict on the other-than-human world. By taking seriously the harms of an other-than-human animal, the film raises important questions of how these harms can and should be redressed, as well as broader questions around how we relate to and empathise with the animal world.

In Memories, (produced by Sonan SOUS, Sreytoch SAT, Theang PAOV), issues of gender and cultural change are explored. Although Bunong cultural practice has tended not to confer the role of mahout (a caretaker of an elephant) to women, Preng Chanthy strives to maintain the traditions of her Indigenous community. The film follows her as she balances caring for the local elephants, brewing rice wine to offer to spirits, and passing her wisdom on to the next generation. In doing so, the film helps to demonstrate how gender is implicated in processes of cultural change and adaptation, particularly as the demands of development come to bare on Bunong communities.

“The most shocking thing is the elephant. Some elephants are traumatized, some elephants are having PTSD. So this surprised me so much that sometimes I even feel that, in our daily life, we are routinely focusing on our lives like going to work or study, we often time forget that there are so many left behind animal in the wild that is in danger… I then realized that even elephants also has mental illness similar to human.” (Choulay Mech, student filmmaker)

The films each mobilise the affective role of elephants (and other wildlife) on screen to convey a sense of precarity and vulnerability around Cambodia’s forests. The films further illustrate the interconnected relationships of Indigenous peoples with forests and forest life by showing, on the one hand, the formative role of the forest in Bunong identity and, on the other, the effects of humans on the forest and the possibility of more sustainable forms of forest management. As such, the films lend themselves as advocacy tools for calling attention to environmental harms and the challenges facing Bunong people.

Indigenous heritage

The films have been produced and edited in Khmer and Bunong languages to ensure that the films are accessible to Bunong Indigenous groups. At a screening in Modulkiri in January 2021, Bunong Indigenous community members spoke of the importance of seeing their stories about the challenges facing their communities represented in Bunong language. The relationships that Bunong communities have had with elephants and forest ecosystems in Cambodia is based upon a distinctive cultural and spiritual worldview that is predicated on the vibrancy and life of the forest. As such, the films can highlight the experiences of Bunong people as valuable and in need of broader social, political, and moral attention. Going further, the films might open up possibilities for wider audiences to engage with and imagine the possibility of other forms of relationship to forests and wildlife that are less extractive and destructive.

“I think the films highlighted a number of very strong and important issues with the first one, looking at the Indigenous people’s knowledge and their relationship with elephants. This something that will come to an end one day. Unfortunately, this knowledge we hope to preserve in the film. That we see in the film we hope to preserve it for the future generation.” (Chris Iverson, ELIE)

It may be that the films can also contribute more broadly to the preservation of Indigenous heritage in Cambodia. The use of Indigenous languages in Cambodia is declining, a reality that reflects broader trends across the world (Walsh 2005). By producing the films in Bunong language, it is hoped that the films will assist with the preservation of Indigenous heritage and tradition. At a screening in Phnom Penh, His Excellency Hab Touch, Secretary of State for the Ministry of Culture, praised the films for their promotion of Indigenous rights: “From father to mother, from grandfather to grandson, this film also brings together the preservation and promotion of awareness of the cultural heritage and good traditions of the indigenous people. »

Building relationships and empathy

The methods of participatory filmmaking adopted in the project provide important lessons for wider arts-led activism around environmental challenges. The recruitment of urban, rural, and Indigenous young Cambodians onto the programme was intended to begin to disrupt the distinctions of “insider” and “outsider” implicit in the participatory tradition (Pauwels 2015). In other words, we sought, at the design stage, to structure the project to tell stories from within – but also across – groups of Indigenous communities and young people in Cambodia. Faithful to the participatory tradition, the process of producing films helped to build relationships and empathy between filmmakers and members of the Bunong community that has extended beyond the filmmaking process.

“I think when we stay afar, we cannot hear their voices, so when we work together with them, when we are on the same path, we listen to them, and when we hear their voices, we will know more regarding the issues.” (Reaksa)

The intersecting relationships of questions of environmental and social justice are again apparent. Indigenous communities in Cambodia often suffer discrimination and exclusion from other Khmer communities because of a perception of indigeneity as ‘primitive’ and ‘uncivilised.’ Destigmatising, demystifying, and familiarising the experiences of Indigenous communities is therefore a necessary part of amplifying awareness of the environmental challenges that Indigenous communities face and vice versa. Similarly, increased empathy with other-than-human creatures is an important facilitator of pro-environmental sentiments and behaviours. Recognising that these challenges affect not just all Cambodians but have regional and international salience is an important step in cultivating a shared sense of responsibility for environmental harms within and across communities. The process of participatory filmmaking is particularly well equipped to do this as both a tool for educators and a medium for advocacy and activism.

Conclusion: Reflecting on participatory film for environmental and social justice

Film has become an increasingly dominant medium for shaping and steering the public imagination of environmental challenges and how they can be apprehended. The attendant challenge for filmmakers is to cultivate connections of these issues across local, national, regional, and global scales, while retaining sensitivity to the necessarily intersecting ‘human’ and environmental injustices that surround them. Our project suggests that actively involving young people and impacted communities (human and other-than-human) in the production of film can play an important role in promoting engagement with these injustices. Going forward, our task will be to mobilise these films as advocacy tools to engage audiences in Cambodia, to demonstrate that issues that face Indigenous communities in Cambodia affect all Cambodians, and to in turn highlight how challenges that appear particular to the Cambodian context have both regional and international resonance and implications.

I wish that my films will be distributed in general. and it can be a message for our country to understand more regarding conservation, especially I want our royal government to see the film as well, because once they watch the film they will participate with us (Pov Theang, student filmmaker)

Recent United Nations policy agendas around “Global Citizenship Education” demonstrate a growing recognition of the importance of engaging young people as promoters of peace, human rights, and sustainability. Young people have further been positioned as a key constituency in the fight against environmental harm and climate change at a global level. We should remain mindful that there are significant hazards around an intergenerational politics that allows the burden of responsibility for taking these challenges on to fall on to young people. But our findings from this programme show the value and potential power of young people’s voices when they are given creative control of authoring stories about environmental and social justice issues.

Looking back at the project, I feel the students were incredibly dedicated and they were very passionate. They had a clear goal and vision about what they wanted to create. They have tried to promote and share the challenges to as many people. And to see that passion from so many young Cambodians, was very humbling. (Chris Iverson, ELIE)

– Project Report in English as PDF : Download

– Project Report in Khmer as PDF : Download

References

Duvall, J.A., 2017. The environmental documentary: Cinema activism in the 21st century. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Maltby M. and Bourchier G. 2011. Current status of Asian elephant in Cambodia. Gajah 35: 36-42.

Pauwels, L., 2015. ‘Participatory’ visual research revisited: A critical-constructive assessment of epistemological, methodological and social activist tenets. Ethnography, 16(1): 95-117.

Walsh, M., 2005. Will Indigenous languages survive? Annual Review of Anthropology, 34: 293-315.

Funded by:

In collaboration with: