Story Behind the Photos

By Paul K. Cummings

Perhaps alone among contributors here, I am neither journalist nor photographer. My business was tourism — I had the rare privilege of visiting Cambodia during an important part of its history, the early years of recovery after the Pol Pot regime. My hope is that I have been able to document something of life from this period, now 40 years in the past.

I am just old enough to remember learning about Cambodia in the 1960s when it was a leading destination in Southeast Asia with its magnificent monuments and friendly people. Celebrities such as Jackie Kennedy used to visit and marvel at the Angkor temples. This ended abruptly in 1970 when Cambodia became engulfed in the Vietnam War, the last tourists fled Angkor, and the country was dragged into a brutal war followed by a bloody revolution.

As we all know, in 1975 Cambodia was captured by the Khmer Rouge and effectively disappeared from the world. For the next three and a half years no contact was possible, at least from a western country. The borders were closed, there were no flights, no embassies, telephone or telex, no mail, nothing. Even airlines flying the normal routes in Asia had to take detours to avoid Cambodian airspace.

I had a small reminder of Cambodia every time I came to land at Bangkok Airport. Sitting on an unused runway for many years were the abandoned French-built Caravelle aircraft of Royal Air Cambodge which had landed in April 1975 as Phnom Penh was falling and whose crews refused to return. Nobody owned those planes anymore. Over the years, the paint faded to the point that it was almost unreadable and finally they were scrapped. It seemed to me a heartbreaking metaphor for the Cambodia that we once knew.

Now that we live in such a connected and globalised world it is easy to forget that not very long ago the world was divided into two mutually hostile blocs with little trade or tourism contact. I sensed a business opportunity and believed that tourism could do some good to promote understanding across the divide. With this in mind, I started a tourist company, Orbitours, and commenced operations in Vietnam and Laos, finally at peace.

Around that time, the Khmer Rouge government was overthrown and that gave me some hope that tourism in Cambodia may be possible one day. I applied for a visa, but I had to wait a couple of years before it was approved.

Finally, in 1983, I arrived in Phnom Penh for the first time. Getting there was challenging. While the fledgling People’s Republic of Kampuchea was willing to cautiously open its doors, it was internationally isolated. There was no embassy in Bangkok and no access from Thailand. However, the airport had reopened and flights had resumed from Ho Chi Minh City. Luckily, I was already becoming quite experienced working in Vietnam.

Phnom Penh had been left mostly uninhabited and decaying for the almost 4 years of Khmer Rouge occupation and after the regime’s overthrow people once more had freedom of movement. Many came from the countryside to find a place to live and search for their families. There was little motor traffic since the Khmer Rouge had junked cars.

Instead, just a few newly imported Russian cars, all belonging to government departments, cruised the streets and cyclos were plentiful, making getting around the city easier than today.

A handful of shops and restaurants were operating, a few hotels were open although power was unreliable and it was necessary to walk up the fire escape to the rooms. The other guests were from socialist countries, international organisations, or else NGO staffers and journalists. Currency had recently been reintroduced (one riel was originally equivalent to a certain quantity of rice) so trade was once again possible. Markets were functioning and quite busy with both local and imported goods, surprisingly with a wider variety of goods than in Vietnam. There was significant aid apparent from the Soviet Bloc including a Hungarian-sponsored orphanage.

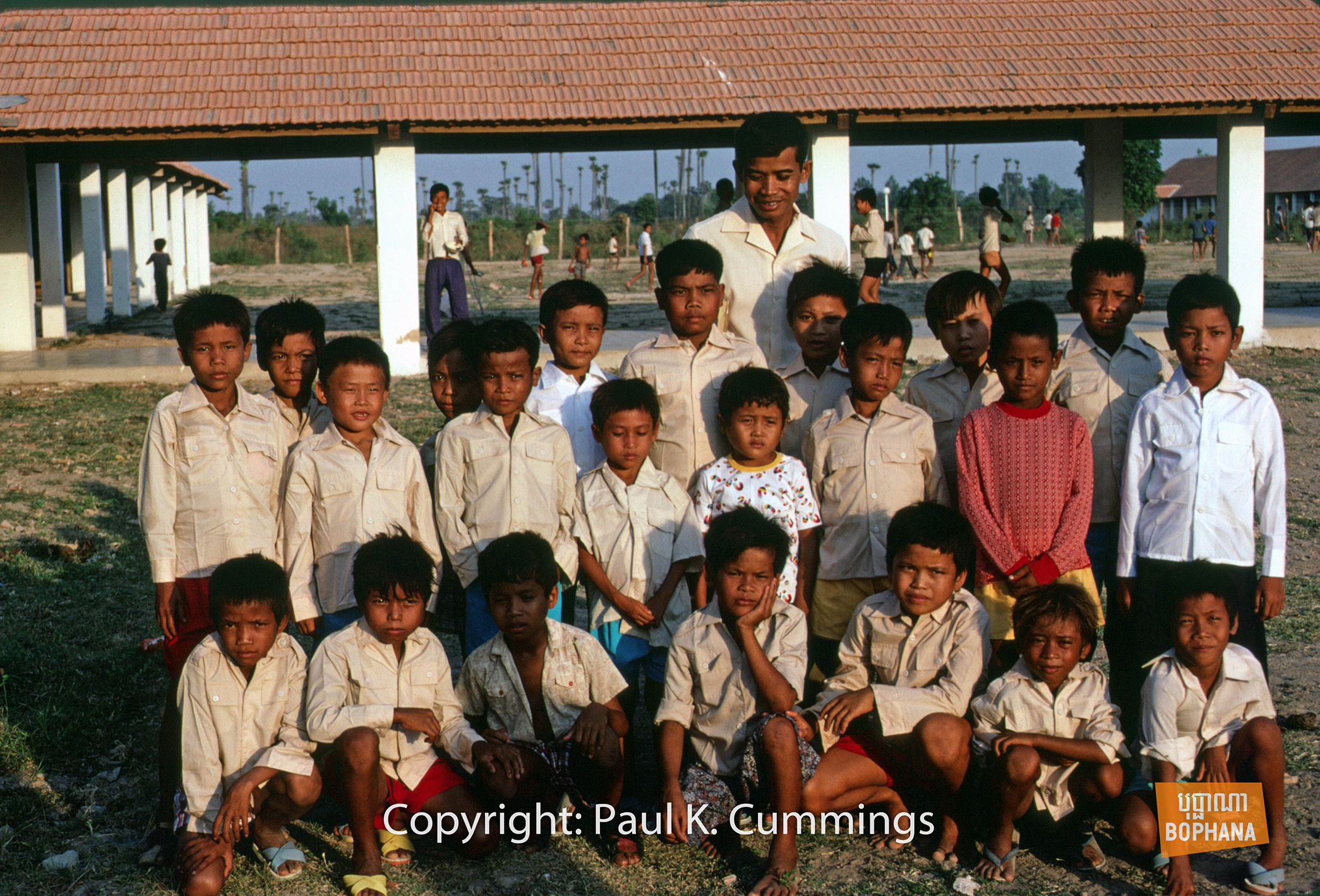

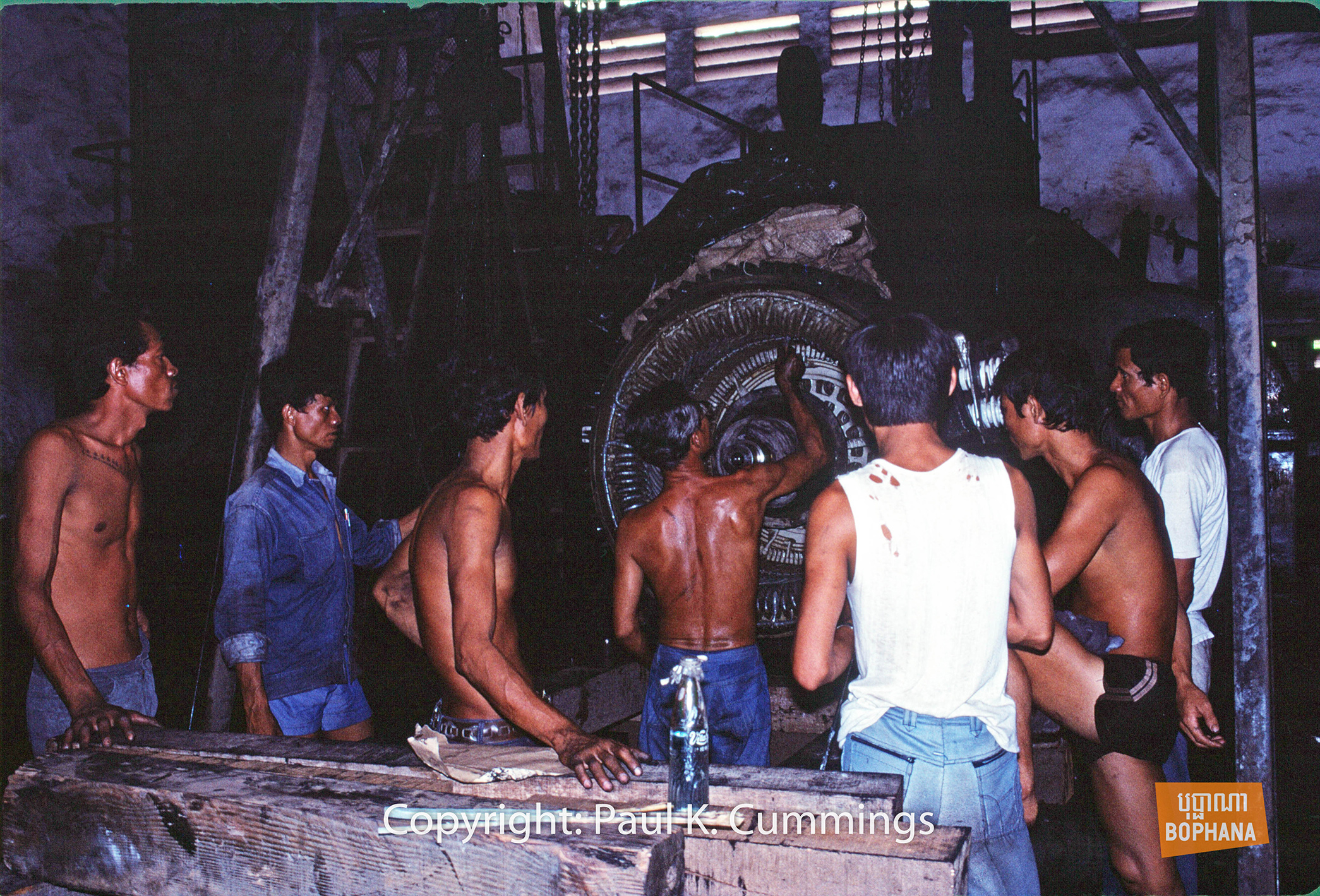

I was able to visit schools, factories making tyres from local rubber and places of higher education such as the medical school.

Communications still had a long way to go. With the local telephone system having fallen into disuse, the telephone lines in Phnom Penh were being repaired one by one and the entire telephone directory of the city covered a single page. It was easier to take a cyclo ride across town than make a telephone call. International communications hardly existed. There was no way to contact home. I carried a shortwave radio, the only way to keep up with the news.

Security was still an issue. There was a curfew at 9 Pm in the city. The highways were in poor condition and not always safe. Shortages of vehicles and fuel made travel between cities difficult.

Toul Sleng Museum and the “Killing Fields” were already open and a chilling experience just as they are today.

We brought our first tourist group comprising multiple nationalities in February 1984, the first to visit both Angkor and Phnom Penh since 1970. The tourists were impressed not just by the temples but also by the determined and resourceful people they met and the considerable news coverage the tour generated which brought a renewed focus on Cambodia.

Finally, in 1991, the Paris Peace Agreement was signed, Prince Sihanouk to return from abroad, elections were planned, United Nations forces landed and a new chapter commenced even as the last of the Khmer Rouge held out for a few more years before surrendering.

• Biography of Paul K. Cummings »

• Return to the “Welcome to Cambodia: From War Zone to Tourist Destination” homepage »